As demand for coronavirus testing surges around the nation, laboratories that process samples are again experiencing backlogs that have left anxious patients and their doctors waiting days — sometimes a week or more — for results.

At the city and state levels, testing delays could mask persistent rises in case numbers and could cloud ways to combat the coronavirus, as health officials continue to find themselves one step behind the virus’s rapid and often silent spread, experts said.

Dr. Francis Collins, the director of the National Institutes of Health, acknowledged the dangers associated with such delays in an interview on NBC’s “Meet the Press” that aired on Sunday.

“The average test delay is too long,” Dr. Collins said. “That really undercuts the value of the testing, because you do the testing to find out who’s carrying the virus, and then quickly get them isolated so they don’t spread it around. And it’s very hard to make that work when there’s a long delay built in.”

Though the coronavirus testing landscape continues to expand, most patient samples must still be routed through laboratories for processing, and the demand is once again straining supplies, equipment and trained technicians and causing shortages.

“It’s very important for people to be able to get the results in time, so they don’t continue infecting people,” said Pamela Martinez, an expert in disease dynamics at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health.

That has become increasingly essential, Dr. Martinez added, as mounting evidence has indicated that the virus can spread from people who don’t have symptoms. “Maybe if I take a test, but I don’t have many symptoms, I’m not going to take the same precautions,” she said.

Health workers typically advise their patients to quarantine at home while they await their test results, out of an abundance of caution. To the extent that one can, “The best thing to do is to act as if you’ve been infected” in this interim period, said Olivia Prosper, an infectious disease modeler at the University of Tennessee, Knoxville. But the longer people are forced to wait, the more difficult that advice is to follow — and the larger toll their absence from work or family responsibilities can take.

Additionally, negative results can be of little use if they are delivered after too long of a delay. Diagnostic testing, which searches for bits of the coronavirus’s genetic material, can only assess a person’s health status from the time the sample was taken, and can’t account for any subsequent exposures to the virus.

Some have held out hope that new, confirmed coronavirus cases could soon peak in certain states, after which parts of the nation might experience a much-needed respite in infections — as, perhaps, some regions did for much of May. But the duration of that apex, which might actually manifest more like a plateau, can’t be definitively forecast. With many laboratories stretched to or past their limits, a leveling-off in confirmed cases could indicate a slowing in the coronavirus’s spread. Or it could simply reflect a regional ceiling in testing capacity.

These scenarios can be difficult to tease apart, Dr. Prosper said. Disease transmission dynamics also undergo some natural flux within populations, as people change their socialization patterns or spend more or less time outdoors. As such, putting too much stock in day-to-day trends can be risky, and possibly misleading.

“We need to be looking at long-term trends,” Dr. Prosper said. “Even if there is a string of days where case counts are lower, that’s not necessarily reflective of a downward trend in this epidemic.”

Researchers also believe that current reported case counts of the coronavirus are vastly undercounting the actual number of infections — a knowledge gap that has made it difficult to quash the virus for good. “Most people will seek a test if they’re showing symptoms,” Dr. Prosper said. But those who feel well often have less incentive to do so.

In an ideal world, she said, far more community testing would occur to catch some of these more silent cases. “That would give us more of an idea of how this disease is actually playing out,” she said.

But laboratories that are hitting their breaking points may be unlikely candidates to bridge that divide.

To speed turnaround times, Dr. Collins said, health officials are pushing for more point-of-care testing — “on the spot” tests designed to be done rapidly and easily, without the need for specialized laboratory equipment or personnel.

Some of these tests could be completed in a doctor’s office, or perhaps even at home, in under an hour. Simple, speedy tests could prove to be a boon for institutions and communities that care for large numbers of vulnerable people, such as nursing homes. They could also help health workers bring testing supplies to populations that have often been denied access to testing and reliable health care, including those marginalized by race, ethnicity or socioeconomic status.

A handful of point-of-care tests have been greenlighted for emergency use by the Food and Drug Administration.

“We need to invest a lot of money, and the government is willing to do so, in scaling those up,” Dr. Collins said on Sunday. “That’s the kind of thing that I personally, along with many others in other parts of the government, are working on night and day to try to do a better job of.”

But Dr. Prosper pointed out that speed often comes at the price of accuracy — an issue that has plagued some point-of-care tests in the past. Though rapid testing can still play a substantial role in mitigating the spread of the coronavirus, researchers will need to remain wary of these trade-offs, she said.

As testing efforts continue to ramp up, Dr. Martinez cautioned that the nation will need to maintain its vigilance for some time yet. “The effects of social distancing are reversible,” she said. If people give up on those strategies too soon, “It’s likely that we will observe a third or a fourth peak. And that could have big implications.”

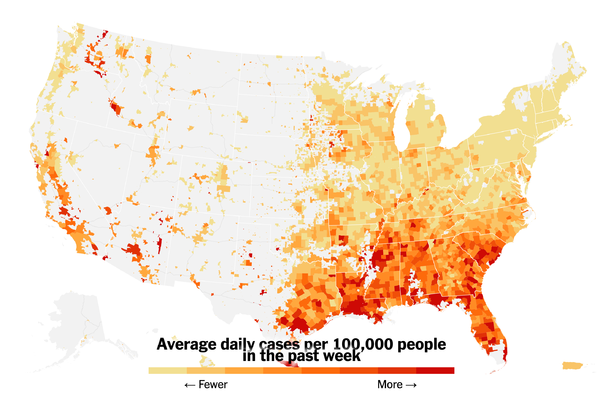

In an interview on Sunday with CBS’s “Face the Nation,” Dr. Scott Gottlieb, the former commissioner of the Food and Drug Administration, reiterated the potentially devastating consequences of failing to rein in the virus, noting spikes in cases in states like California, Texas, Arizona and Florida. He warned that other states, like Georgia, Tennessee and Kentucky, could follow similar patterns.

“We’re seeing record numbers of cases, rising hospitalizations and really a shifting of the center of the epidemic potentially in the United States,” Dr. Gottlieb said. “This just portends more trouble for the fall and the winter, that we’re going to be taking a lot of infection into the fall, that we’re never going to really be able to come down.”