The Wuhan coronavirus spreading from China is now likely to become a pandemic that circles the globe, according to many of the world’s leading infectious disease experts.

The prospect is daunting. A pandemic — an ongoing epidemic on two or more continents — may well have global consequences, despite the extraordinary travel restrictions and quarantines now imposed by China and other countries, including the United States.

Scientists do not yet know how lethal the new coronavirus is, however, so there is uncertainty about how much damage a pandemic might cause. But there is growing consensus that the pathogen is readily transmitted between humans.

The Wuhan coronavirus is spreading more like influenza, which is highly transmissible, than like its slow-moving viral cousins, SARS and MERS, scientists have found.

“It’s very, very transmissible, and it almost certainly is going to be a pandemic,” said Dr. Anthony S. Fauci, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease.

“But will it be catastrophic? I don’t know.”

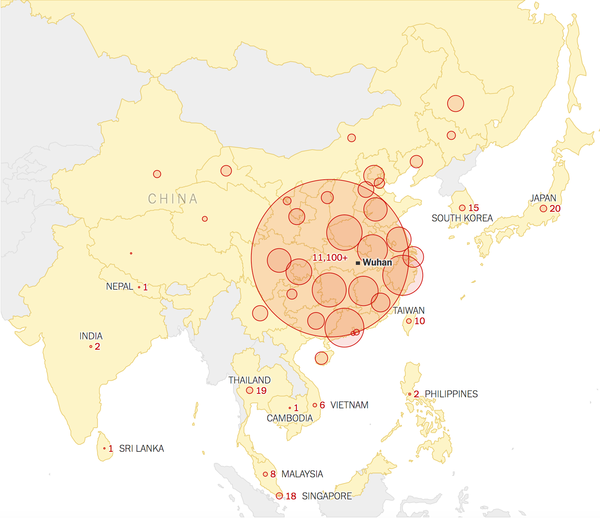

In the last three weeks, the number of lab-confirmed cases has soared from about 50 in China to more than 17,000 in at least 23 countries; there have been more than 360 deaths.

But various epidemiological models estimate that the real number of cases is 100,000 or even more. While that expansion is not as rapid as that of flu or measles, it is an enormous leap beyond what virologists saw when SARS and MERS emerged.

When SARS was vanquished in July 2003 after spreading for nine months, only 8,098 cases had been confirmed. MERS has been circulating since 2012, but there have been only about 2,500 known cases.

The biggest uncertainty now, experts said, is how many people around the world will die. SARS killed about 10 percent of those who got it, and MERS now kills about one of three.

The 1918 “Spanish flu” killed only about 2.5 percent of its victims — but because it infected so many people and medical care was much cruder then, 20 to 50 million died.

By contrast, the highly transmissible H1N1 “swine flu” pandemic of 2009 killed about 285,000, fewer than seasonal flu normally does, and had a relatively low fatality rate, estimated at .02 percent.

The mortality rate for known cases of the Wuhan coronavirus has been running about 2 percent, although that is likely to drop as more tests are done and more mild cases are found.

It is “increasingly unlikely that the virus can be contained,” said Dr. Thomas R. Frieden, a former director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention who now runs Resolve to Save Lives, a nonprofit devoted to fighting epidemics.

“It is therefore likely that it will spread, as flu and other organisms do, but we still don’t know how far, wide or deadly it will be.”

In the early days of the 2009 flu pandemic, “they were talking about Armageddon in Mexico,” Dr. Fauci said. (That virus first emerged in pig-farming areas in Mexico’s Veracruz State.) “But it turned out to not be that severe.”

An accurate estimate of the virus’s lethality will not be possible until certain kinds of studies can be done: blood tests to see how many people have antibodies, household studies to learn how often it infects family members, and genetic sequencing to determine whether some strains are more dangerous than others.

Closing borders to highly infectious pathogens never succeeds completely, experts said, because all frontiers are somewhat porous. Nonetheless, closings and rigorous screening may slow the spread, which will buy time for the development of drug treatments and vaccines.

Other important unknowns include who is most at risk, whether coughing or contaminated surfaces are more likely to transmit the virus, how fast the virus can mutate and whether it will fade out when the weather warms.

The effects of a pandemic would probably be harsher in some countries than in others. While the United States and other wealthy countries may be able to detect and quarantine the first carriers, countries with fragile health care systems will not. The virus has already reached Cambodia, India, Malaysia, Nepal, the Philippines and rural Russia.

“This looks far more like H1N1’s spread than SARS, and I am increasingly alarmed,” said Dr. Peter Piot, director of the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine. “Even 1 percent mortality would mean 10,000 deaths in each million people.”

Other experts were more cautious.

Dr. Michael Ryan, head of emergency responses for the World Health Organization, said in an interview with STAT News on Saturday that there was “evidence to suggest this virus can still be contained” and that the world needed to “keep trying.”

Dr. W. Ian Lipkin, a virus-hunter at the Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health who is in China advising its Center for Disease Control and Prevention, said that although the virus is clearly being transmitted through casual contact, labs are still behind in processing samples.

But life in China has radically changed in the last two weeks. Streets are deserted, public events are canceled, and citizens are wearing masks and washing their hands, Dr. Lipkin said. All of that may have slowed down what lab testing indicated was exponential growth in the infection.

It’s unclear exactly how accurate tests done in overwhelmed Chinese laboratories are. On the one hand, Chinese state media have reported test kit shortages and processing bottlenecks, which could produce an undercount.

But Dr. Lipkin said he knew of one lab running 5,000 samples a day, which might produce some false-positive results, inflating the count. “You can’t possibly do quality control at that rate,” he said.

Anecdotal reports from China, and one published study from Germany, indicate that some people infected with the Wuhan coronavirus can pass it on before they show symptoms. That may make border-screening much harder, scientists said.

Epidemiological modeling released Friday by the European Center for Disease Prevention and Control estimated that 75 percent of infected people reaching Europe from China would still be in the incubation periods upon arrival, and therefore not detected by airport screening, which looks for fevers, coughs and breathing difficulties.

But if thermal cameras miss victims who are beyond incubation and actively infecting others, the real number of missed carriers may be higher than 75 percent.

Still, asymptomatic carriers “are not normally major drivers of epidemics,” Dr. Fauci said. Most people get ill from someone they know to be sick — a family member, a co-worker or a patient, for example.

The virus’s most vulnerable target is Africa, many experts said. More than 1 million expatriate Chinese work there, mostly on mining, drilling or engineering projects. Also, many Africans work and study in China and other countries where the virus has been found.

If anyone on the continent has the virus now, “I’m not sure the diagnostic systems are in place to detect it,” said Dr. Daniel Bausch, head of scientific programs for the American Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene, who is consulting with the W.H.O. on the outbreak.

South Africa and Senegal could probably diagnose it, he said. Nigeria and some other countries have asked the W.H.O. for the genetic materials and training they need to perform diagnostic tests, but that will take time.

At least four African countries have suspect cases quarantined, according to an article published Friday in The South China Morning Post. They have sent samples to France, Germany, India and South Africa for testing.

[Like the Science Times page on Facebook. | Sign up for the Science Times newsletter.]

At the moment, it seems unlikely that the virus will spread widely in countries with vigorous, alert public health systems, said Dr. William Schaffner, a preventive medicine specialist at Vanderbilt University Medical Center.

“Every doctor in the U.S. has this top of mind,” he said. “Any patient with fever or respiratory problems will get two questions. ‘Have you been to China? Have you had contact with anyone who has?’ If the answer is yes, they’ll be put in isolation right away.”

Assuming the virus spreads globally, tourism to and trade with countries besides China may be affected — and the urgency to find ways to halt the virus and prevent deaths will grow.

It is possible that the Wuhan coronavirus will fade out as weather warms. Many viruses, like flu, measles and norovirus, thrive in cold, dry air. The SARS outbreak began in winter, and MERS transmission also peaks then, though that may be related to transmission in newborn camels.

Four mild coronaviruses cause about a quarter of the nation’s common colds, which also peak in winter.

But even if an outbreak fades in June, there could be a second wave in the fall, as has occurred in every major flu pandemic, including those that began in 1918 and 2009.

By that time, some remedies might be on hand, although they will need rigorous testing and perhaps political pressure to make them available and affordable.

In China, several antiviral drugs are being prescribed. A common combination is pills containing lopinavir and ritonavir with infusions of interferon, a signaling protein that wakes up the immune system.

In the United States, the combination is sold as Kaletra by AbbVie for H.I.V. therapy, and it is relatively expensive. In India, a dozen generic makers produce the drugs at rock-bottom prices for use against H.I.V. in Africa, and their products are W.H.O.-approved.

Another option may be an experimental drug, remdesivir, on which the patent is held by Gilead. The drug has not yet been approved for use against any disease. Nonetheless, there is some evidence that it works against coronaviruses, and Gilead has donated doses to China.

Several American companies are working on a vaccine, using various combinations of their own funds, taxpayer money and foundation grants.

Although modern gene-chemistry techniques have made it possible to build vaccine candidates within just days, medical ethics require that they then be carefully tested on animals and small numbers of healthy humans for safety and effectiveness.

That aspect of the process cannot be sped up, because dangerous side effects may take time to appear and because human immune systems need time to produce the antibodies that show whether a vaccine is working.

Whether or not what is being tried in China will be acceptable elsewhere will depend on how rigorously Chinese doctors run their clinical trials.

“In God we trust,” Dr. Schaffner said. “All others must provide data.”