November 7, 2018

Mary Chris Jaklevic is a reporter-editor at HealthNewsReview.org. She tweets as @mcjaklevic.

Wake me when it’s over.

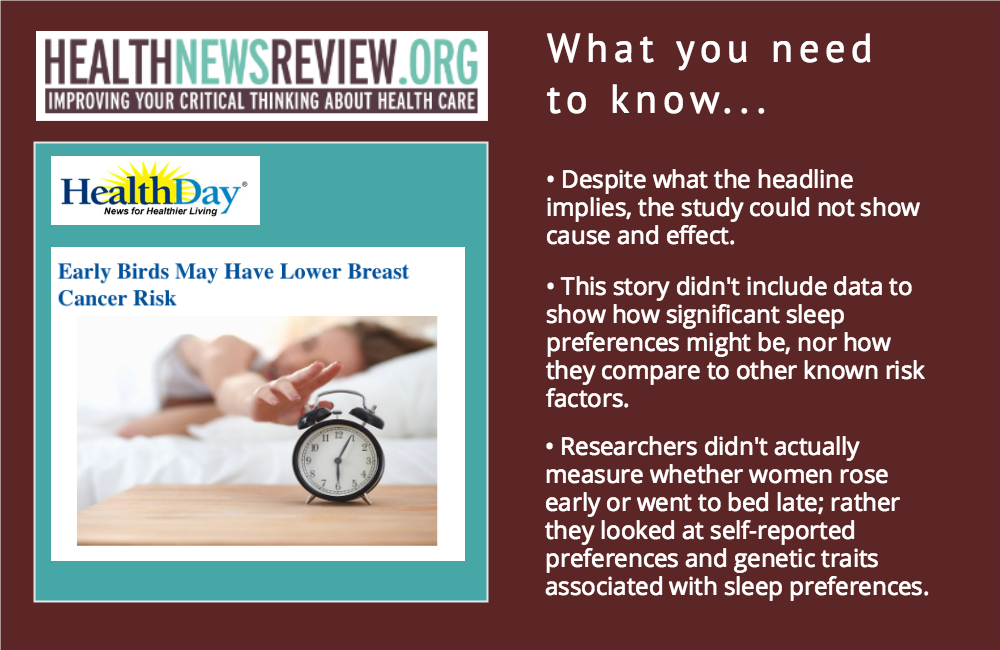

There was a lot of misleading information in news stories this week about a study of sleep traits and risk of breast cancer. It was a complex study to decipher, but instead we got simplistic headlines like this one from HealthDay: “Early Birds May Have Lower Breast Cancer Risk.”

That story stated: “Compared to night owls, women who are early risers had a 40 percent lower risk of breast cancer, the study found.”

Forty percent lower risk? No, not really. Despite what readers might glean from this story and others, this research did not prove that getting up early lowers a woman’s breast cancer risk.

Moreover, it did not even show an association between getting up early and reduced breast cancer risk.

Research didn’t look at when women slept

What HealthDay didn’t make clear to readers is that researchers didn’t actually look at whether women rose early or went to bed late. Rather, they analyzed data from two databases encompassing about 400,000 women. They examined women’s self-reported responses when asked where the fell on a scale between being a “morning person” and being an “evening person” as well as genetic variations associated with sleep preferences.

HealthDay also didn’t provide real numbers to indicate how much of a difference a “40 percent lower risk” might represent—nor how sleep preferences might compare with established risk factors for breast cancer. For more information on why it’s important to include real numbers, see our primer on absolute versus relative risk.

The story said “women who slept longer than the recommended seven to eight hour a night had a 20 percent increased risk of breast cancer for each additional hour slept.” That data, too, is problematic because it was based on women’s self-reporting of how much they slept. The story did not explain how that data was collected.

To its credit, HealthDay clarified that the study “did not prove a cause-and-effect relationship between sleeping patterns and breast cancer risk” and quoted a researcher who said “it may not be the case that changing your habits changes your risk of breast cancer.”

But those caveats appeared several paragraphs into the story, where readers might not notice them. Moreover, the story included other quotes that were less cautious and seemingly contradictory, such as one referring to “a protective effect” of morning sleep preference.

CNN better explored caveats

Stories on this research also ran in BBC News, CNN, and USA Today. All appeared to take their cues from a misleading news release entitled “Women who are ‘larks’ have a lower risk of developing breast cancer.”

BBC News was the only one of the four we looked at that provided absolute data. It wrote that the study “only looked at a small, eight-year snapshot of a woman’s life,” during which time “it showed two in 100 owls developed breast cancer compared with one in 100 larks.”

CNN did the most complete job of explaining the evidence. It mentioned caveats missed by other stories:

- It’s unclear whether the findings can be applied across populations because the analysis was restricted to women of European ancestry.

- Sleep habits may not be as significant as established breast cancer risk factors such as body-mass index or alcohol use.

- There is no known reason why preferring to get up early would stave off breast cancer.

A research method called Mendelian randomization was mentioned in all of the stories except HealthDay’s. Only CNN discussed its limitations, quoting a researcher who said, “The statistical method used in this study, called Mendelian randomization, does not always allow causality to be inferred.”

As a BMJ primer explains, the method “depends on assumptions, and the plausibility of these assumptions must be assessed. Moreover, the relevance of the results for clinical decisions should be interpreted in light of other sources of evidence.”

So, even though we can expect to hear much more about this method as it’s used to study the role of genetic variants in health outcomes, it is still dicey to tell the public that cause-and-effect has been undeniably established.

An unpublished study that hasn’t been peer-reviewed

All of the stories noted that the study wasn’t in a peer-reviewed journal; an abstract was presented at a medical conference.

The fact that this research hasn’t been published is one more reason why the data can’t be considered reliable. The validity and importance of unpublished research often hasn’t been established, as our primer on news from scientific meetings explains.

So as far as this report goes, sleep tight — whenever you please.