NAIROBI, Kenya — Four days after her toddler’s health took a turn for the worse, his tiny body wracked by fever, diarrhea and vomiting, Sharon Mbone decided it was time to try yet another medicine.

With no money to see a doctor, she carried him to the local pharmacy stall, a corrugated shack near her home in Kibera, a sprawling impoverished community here in Nairobi. The shop’s owner, John Otieno, listened as she described her 22-month-old son’s symptoms and rattled off the pharmacological buffet of medicines he had dispensed to her over the previous two weeks. None of them, including four types of antibiotics, were working, she said in despair.

Like most of the small shopkeepers who provide on-the-spot diagnosis and treatment here and across Africa and Asia, Mr. Otieno does not have a pharmacist’s degree or any medical training at all. Still, he confidently reached for two antibiotics that he had yet to sell to Ms. Mbone.

“See if these work,” he said as she handed him 1,500 shillings for both, about $ 15.

[Like the Science Times page on Facebook. | Sign up for the Science Times newsletter.]

Antibiotics, the miracle drugs credited with saving tens of millions of lives, have never been more accessible to the world’s poor, thanks in large part to the mass production of generics in China and India. Across much of the developing world, it costs just a few dollars to buy drugs like amoxicillin, a first-line antibiotic that can be used against a broad range of infections, from bacterial pneumonia and chlamydia to salmonella, strep throat and Lyme disease.

Kibera residents are prodigious consumers of antibiotics. One study found that 90 percent of households in Kibera had used antibiotics in the previous year, compared with about 17 percent for the typical American family.

But the increasing availability of antibiotics has accelerated an alarming downside: The drugs are losing their ability to kill the germs they were created to conquer. Hard-wired to survive, many bacteria have evolved to outsmart the medications.

And as these mutant bacteria commingle with other pathogens in sewage canals, hospital wards and livestock pens, they can share their genetic resistance traits, making other micro-organisms impervious to antibiotics.

Antibiotic resistance is a global threat, but it is often viewed as a problem in rich countries, where comfortably insured patients rush to the doctor to demand prescriptions at the slightest hint of a cough or cold.

In fact, urban poverty is a huge and largely unappreciated driver of resistance. And so, the rise of resistant microbes is having a disproportionate impact on poor countries, where squalid and crowded living conditions, lax oversight of antibiotic use and a scarcity of affordable medical care are fueling the spread of infections increasingly unresponsive to drugs.

“We can’t effectively mitigate the growing problem of antibiotic resistance without dealing with places like Kibera,” said Dr. Guy H. Palmer, a researcher at Washington State University who studies resistance in Africa. “There are a billion people living in similar situations, and as long as they aren’t getting clean water and basic sanitation, all of us are at risk.”

Worldwide, resistant pathogens already claim 700,000 lives each year, according to one British study. Resistance here in Kenya is not just a potential calamity for future generations: Lack of effective treatment is already claiming thousands of lives each year, many of them young children whose immune systems have yet to fully develop, according to government figures.

Sam Kariuki, a researcher at the Kenya Medical Research Institute who has been studying resistance for two decades, said nearly 70 percent of salmonella infections in Kenya had stopped responding to the most widely available antibiotics, up from 45 percent in the early 2000s.

Salmonella kills roughly 45,000 Kenyan children every year, or nearly one in three who fall severely ill with it, he said. In the United States, the mortality rate is close to zero.

“We are quickly running out of treatment options,” Professor Kariuki said. “If we don’t get a handle on the problem, I fear for the future.”

In some cases, vendors sell counterfeit antibiotics that contain none of the active ingredient, or so little that they accelerate resistance. Even when the drugs are authentic, many poor Kenyans try to save money by buying just a few tablets instead of the full course — not enough to vanquish an infection but enough to allow bacteria to mutate and gain resistance.

“Who am I to deny them what they want?” asked Lena Ochomba, 40, a pharmacy stall owner in Kibera who earns most of her income selling antibiotics, often three or four pills at a time — an amount that is one-third or less of the recommended course for most antibiotics. “Even when I manage to sell the whole box, my customers rarely take them all because they think it’s just too many pills.”

Poor sanitation, rampant disease

There is no escaping human waste in Kibera. It oozes from shallow, hand-dug latrines, pools into rivulets and finally builds into a black river.

At night, feces-filled plastic bags are tossed from rooftops by those afraid to venture outdoors. Residents call them flying toilets.

Ms. Mbone and her husband have become inured to the sight and smell of untreated sewage that flows in front of their one-room shack. With no other place to play, their son, Shane, and his 3-year-old sister sometimes end up frolicking in the muck. “They are kids, they will always go outside to play,” said Ms. Mbone, 19. “How can you stop them?”

A plastic bucket brimming with store-bought medicine is a testament to the ailments that have dogged Shane for most of his short life. Born prematurely, he spent his first few weeks in a clinic and then at a hospital. Even with subsidized care, the medical bills came to roughly $ 200, equivalent to 10 months of wages that Ms. Mbone’s husband earns as a bus station porter. Since then, she has been reluctant to take Shane to a doctor. “I’m worried if I go to a bigger hospital, the bill will be bigger too,” she said.

Ms. Mbone isn’t convinced that the unsanitary conditions are to blame for Shane’s health problems. Other children play in Kibera’s drainage ditches, she noted, while few are bedeviled by the constant diarrhea that afflicts her son.

But epidemiologists and public health experts who have studied Kibera say there is a direct correlation between the community’s poor hygiene and the infections that stalk nearly every household. Harmful bacteria in feces that is allowed to seep into the surrounding soil can survive for months, and in densely populated settlements like Kibera that are veined with dirt paths, they easily find their way into food and water, often by residents who unknowingly carry the pathogens into their homes on shoes or unwashed hands.

According to a 2012 study by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, cases of typhoid fever among children in Kibera were 15 times higher than those living in a rural area west of the capital; infections in Kibera were even higher in low-lying areas where sewage tends to pool. The study also found that 75 percent of the typhoid strains found there were resistant to commonly available antibiotics.

“A lack of sanitation leads to more disease, which leads to higher antibiotic use, which leads to greater resistance,” said Marc-Alain Widdowson, principal deputy director of the C.D.C.’s Division of Global Health Protection for Kenya, which has been doing surveillance work in Kibera since 1979. “It’s a vicious cycle.”

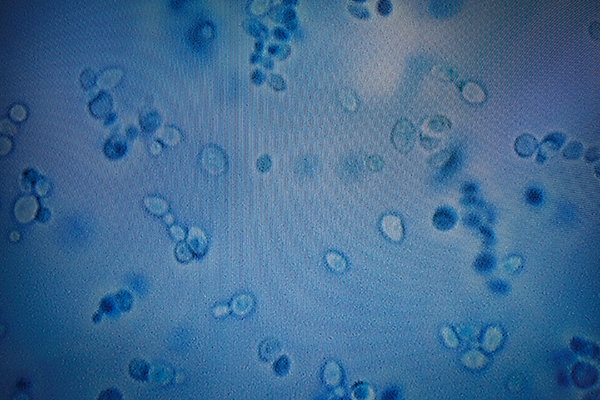

Sylvia Adhiambo Omulo, a researcher at Washington State University’s global health program who has spent the past several years studying antimicrobial resistance in Kibera, said she was stunned by the ubiquity of resistant pathogens like E. coli.

“It’s in the soil, it’s on the kale people eat, and also on the hands of adults and children,” she said one afternoon as she trudged through Kibera’s muddy footpaths, dodging children, stray dogs and the occasional chicken. “It’s no wonder people here are constantly sick.”

When residents feel unwell, they often turn to people like Mr. Otieno, the roadside drug vendor who wears a white lab coat and keeps the bulb in his stall burning late into the night.

Ms. Mbone relies on him for affordable drugs, but also for a sympathetic ear and the occasional cash loan. “These chemists are my neighbors,” she said. “I trust their advice.”

A wiry man with sharp features and a gentle manner, Mr. Otieno, 32, is a lifelong resident of Kibera. Unable to find full-time work after high school, he spent several years assisting another chemist in the neighborhood until he saved up enough money for his shop.

With its baby blue interior, medical posters on the wall and a cabinet overflowing with bandages, Mr. Otieno’s stall could be mistaken for a health clinic. Despite his lack of training, he said years of hands-on experience informed his prescribing decisions, and he knows the antibiotics aren’t working because they often don’t cure the people who buy them.

“There’s a lot of antibiotic resistance here,” he said. “That is why people keep coming back to get different antibiotics.”

After cycles of antibiotics, limited options

If Ntihinyuirwa Thade had been conscious, the doctors at Kijabe Mission Hospital would have asked about his medical history, including a list of antibiotics he had taken in recent years. But Mr. Thade, 25, a migrant laborer from Rwanda, was on a ventilator and unconscious, having fallen from the upper floor of a building project. He was not wearing a hard hat and suffered a grievous head injury.

A week after the accident, he was facing a more immediate threat: A Klebsiella pneumonia infection was blossoming in his lungs. Mr. Thade’s condition failed to respond to the three antibiotics already flushed into his veins, so his doctor, George Otieno (no relation to Mr. Otieno, the pharmacy stall owner), was preparing to administer the final drug in his limited arsenal, a relatively expensive antibiotic called meropenem. “If that doesn’t work…,” he said, his voice trailing off.

Klebsiella bacteria are omnipresent in the environment — in the soil and in the human gut — but they can turn deadly for people with frayed immunities.

Dr. Otieno acknowledged that Mr. Thade most likely acquired his through the plastic breathing tube that was keeping him alive.

Many of the world’s leading medical institutions struggle with resistant microbes and Kijabe, one of Kenya’s best hospitals, is no different.

Nestled in a verdant valley just outside Nairobi, it boasts top-notch equipment and a mix of Kenyan and foreign doctors that draw patients from across the country. But being a referral hospital has a downside: Many people arrive quite sick and have already cycled through a plethora of antibiotics. “Oftentimes they have taken every drug that is commonly available,” said Dr. Evelyn Mbugua, an internist.

Mr. Thade was one of several patients that day struggling to overcome resistant bugs. In the pediatric ward, a one-month-old baby, Blessing Karanja, was fighting a worrisome blood infection, and elsewhere in the hospital, Grace Mutiga, 65, a retired nurse, was back again with a tenacious respiratory infection.

Having taken five different antibiotics over the previous few weeks — drugs purchased at the local pharmacy — Ms. Mutiga was running out of options. “We’ll have to see if we can get an antibiotic from Nairobi,” a doctor said as Ms. Mutiga struggled to catch her breath.

In Kenya and other emerging economies, the most effective antibiotics are not always available, or affordable. Loice Achieng, an infectious disease doctor at Kenyatta National Hospital, shook her head when recalling one recent patient, a 65-year-old kidney transplant recipient infected with Pseudomonas aeruginosa, a bacterial illness that is often acquired in hospitals.

After the patient had taken every appropriate antibiotic available in Kenya, Dr. Achieng told the family their only hope was Avycaz, a four-year-old, American-made drug. There were hurdles, however, including red tape from Kenyan customs officials and a $ 10,000 price tag for a 10-day course. After several days, his children managed to gather the necessary funds, but it was too late. The man died.

‘I don’t have faith that we will solve this’

Kenya has officially embraced what public health experts call antimicrobial stewardship, the effort to stem resistance by reducing the overuse of antibiotics, promoting vaccinations and encouraging better hygiene among hospital workers. Over the past two years many of the country’s medical institutions have established stewardship committees. Wall-mounted hand sanitizers have become a common sight in hospital hallways and patient waiting areas.

But the government has made little headway in enforcing laws that require prescriptions for buying antibiotics, nor has it done much to stem the flow of bootleg drugs that spill across the nation’s 400-mile border with Somalia.

“It’s proving more difficult than we thought,” said Dr. Widdowson of the C.D.C., who has been advising the government.

Back at Kijabe Hospital, Mr. Thade’s condition was growing more dire. As nurses prepared him for yet another X-ray, Dr. Otieno talked about the challenges of tackling drug resistance.

A passionate man with wide, expressive eyes, Dr. Otieno, 36, is a driving force behind the hospital’s newly established antimicrobial stewardship program. But he expressed frustration over the lack of progress, describing overworked nurses reluctant to embrace complex hygiene protocols and the hospital’s own pharmacy, which he said continued to overprescribe antibiotics.

“To be honest, based on the past, I don’t have faith that we will solve this. I don’t think our government thinks it’s a big problem,” he said, as Mr. Thade’s limp, swollen body was lifted onto a gurney.

“I worry about my country, but also about my own family. One day I could go home and infect my own children with one of these dangerous bugs.”

In the days that followed, Mr. Thade’s condition stabilized enough that he was moved out of the intensive care unit. Though his injuries prevented him from walking, he regained consciousness and seemed to be recovering, his doctors said, but the infection was tenacious and gave no ground to meropenem, the best antibiotic in the hospital’s arsenal. Three months later, after the infection spread to his blood, Mr. Thade died alone in his bed and far from home. “God rest his soul,” Dr. Otieno said.