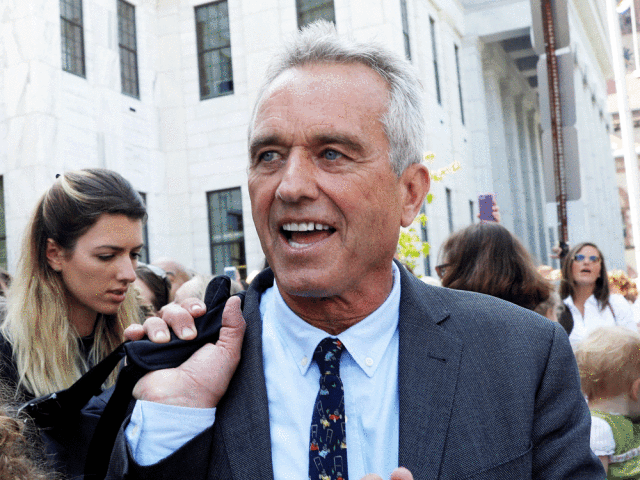

Robert F. Kennedy Jr. and other anti-vaccine crusaders have long and falsely blamed vaccines for breeding an “epidemic” of autism.

But is the epidemic even real?

According to the authors of a new study, the astonishing explosion in the number of diagnosed cases of autism is the result of a broadening of the definition of what counts as “autism” — so much so that the differences between people diagnosed with autism and the rest of the population are shrinking.

“The pretend epidemic of autism is related to the inclusion of people less and less different from non-autistics,” said co-author Dr. Laurent Mottron, a professor in the Université de Montréal’s department of psychiatry.

In research published this week in JAMA Psychiatry, Mottron and colleagues reviewed 11 meta-analyses (studies of studies) published between 1966 and 2019 that compared individuals with and without autism.

The pretend epidemic of autism is related to the inclusion of people less and less different from non-autistics

The researchers were interested in how the “effect size” — a measure of the magnitude of the differences observed between people with autism and people without it — changed over time.

The studies combined included nearly 23,000 people diagnosed with autism.

In almost every trait assessed, including “emotion recognition” — the ability to recognize emotions in other people — and brain size (studies have shown that people with autism will, on average, have a slightly larger brain volume), the measurable differences shrank by 45 to 80 per cent.

“This means that, across all disciplines, the people with or without autism who are being included in studies are increasingly similar,” Mottron said in a release issued with this week’s study. “If this trend holds, the objective difference between people with autism and the general population will disappear in less than 10 years.

“The definition of autism,” Mottron added, “may get too blurry to be meaningful — trivializing the condition — because we are increasingly applying the diagnosis to people whose differences from the general population are less pronounced.”

The finding might explain why no major discoveries have been made in autism in the last decade, he said, because studies are being watered down with too many people with mild and dubious symptoms who aren’t sufficiently different from people without true autism.

It also suggests that any child, or adult, with symptoms loosely resembling autism is now being labelled “autistic,” overwhelming specialty clinics and other services and making it harder for those truly in need to get help.

Autism was first described in the 1940s. In the 1960s, severe autism was thought to affect five to 10 children for every 10,000. By 2014, the estimate was one child in 59, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

There is no gold standard, no biological marker such as a blood test, “to tell you this one is autistic, this one is not,” Mottron said in an interview. “People tried all possible solutions, but with the constant enlargement of the criteria.”

The diagnostic criteria have not only been broadened, they’ve been more loosely applied, he said.

For example: “Fifty years ago, one sign of autism was a lack of apparent interest in others. Nowadays it’s simply having fewer friends than others,” Mottron said. Another symptom was fewer facial expressions. “Twenty years ago you would ask for a complete absence of facial expression. Now it’s less facial expression, fewer friends, less reciprocity — it’s become more and more fuzzy.”

His concern is that many neurodevelopment conditions such as Tourette’s syndrome or ADHD can now be labelled “autistic.”

“You could not be ADHD and autistic before 2013. Now you can,” he said.

“This is justified in some cases where people have both presentations. But it also authorizes to label as autistic pure ADHD people.”

His team found that older studies mostly included people with an “autism” diagnosis, whereas newer studies most often used mixtures of people with an autism, Asperger syndrome or the more catch-all “autism spectrum disorder” diagnosis.

Some experts say the floodgates to over-diagnosis opened in 1994, when the American Psychiatric Association released the fourth edition of its Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, the so-called “bible” of mental illness.

“Probably the biggest mistake we made in DSM-IV was including Asperger’s, a much milder form of autistic disorder with unclear boundaries to normal diversity, eccentricity and giftedness,” said Dr. Allen Frances, who chaired the task force that produced the DSM-IV. Until then, autism was more narrowly defined.

Field trials suggested merging Asperger syndrome with autism would increase the rate of autism three-fold, said Frances, emeritus professor of psychiatry at Duke University. Instead, “Careless diagnosis, often related to requirements for extra school services, resulted in a fake epidemic — a 50-fold increase in the past 25 years.”

You could not be ADHD and autistic before 2013. Now you can

The fifth (and current) edition of the manual, DSM-5, made things worse by collapsing classic autism and Asperger’s into a “spectrum” that makes it even easier to misdiagnose, Frances said.

The unintended consequences, he said, have been “disastrous.”

“Panicked parents falsely assumed the rapid increase in rates was due to vaccination — not realizing it was instead a consequence of looser definitions and assessments. This has led to measles epidemics all over the world.”

Over-diagnosis is also harmful for parents and children, he said — “stigmatizing them, causing needless worry and reducing expectations.”

Mottron (who believes adding Asperger’s to the DSM was, in itself, a good decision) said that health professionals should clearly distinguish autistic traits from autism. Only about 35 per cent of those referred to him for an assessment of autism actually have the disorder.

His team didn’t assess every area where people with autism are known to differ from people without. Still, “The cliché that you will see everywhere is, ‘oh, you have more autism because they are better recognized,’ which is absolutely wrong,” he said.

“It’s not that they are better recognized,” he said. It’s that people with less profound deviations from “normal” are being diagnosed with autism.

• Email: skirkey@postmedia.com Twitter: sharon_kirkey