WASHINGTON — The burdensome costs of medical care, prescription drugs and health insurance have become dominant issues in the 2020 presidential campaign. But a new report from the Department of Health and Human Services shows the nation remains in a period of relatively slow growth in health spending.

Health spending in the United States rose by 4.6 percent to $ 3.6 trillion in 2018 — accounting for 17.7 percent of the economy — compared to a growth rate of 4.2 percent in 2017. Federal officials said the slight acceleration was largely the result of reinstating a tax on health insurers that the Affordable Care Act imposed but Congress had suspended for a year in 2017. Faster growth in medical prices and prescription drug spending were also factors, they said, but comparatively minor.

For decades, national health spending galloped ahead of spending in the overall economy, lowering wages and stressing household budgets. But over the last decade, the pattern has shifted somewhat. Although the country consistently spends more on health care each year than it did the year before, the overall rate of growth has stayed below historical averages. In 2018, health spending grew more slowly than the economy overall, a rare occurrence.

The factors leading to the slowdown are not fully understood. For years, economists thought they were the result of lagging effects of the recession. But as the pattern has continued far into the economic recovery, they increasingly point to changes in the delivery of health care itself.

“Spending has to slow down when it gets so big,” said Paul Hughes-Cromwick, the co-director of sustainable health spending strategies at the research group Altarum. “There’s no question that there are efforts all across the environment to try to control this beast. There’s no question about that, and some of them are working.”

The slower growth may feel at odds with the experience of many Americans, who increasingly report financial duress from health costs. A recent study from the Kaiser Family Foundation, a nonprofit health research organization, found that from 2009 through 2018 individuals who got insurance through their employers have been asked to shoulder an ever-higher share of their health bills through premium payments and rising deductibles. A typical employer plan for an individual now comes with a $ 1,400 deductible, up $ 900 from 2009.

The new report found that overall growth in household health care spending, including out-of-pocket expenses, premium payments and contributions to Medicare through payroll taxes, remained flat, at 4.4 percent.

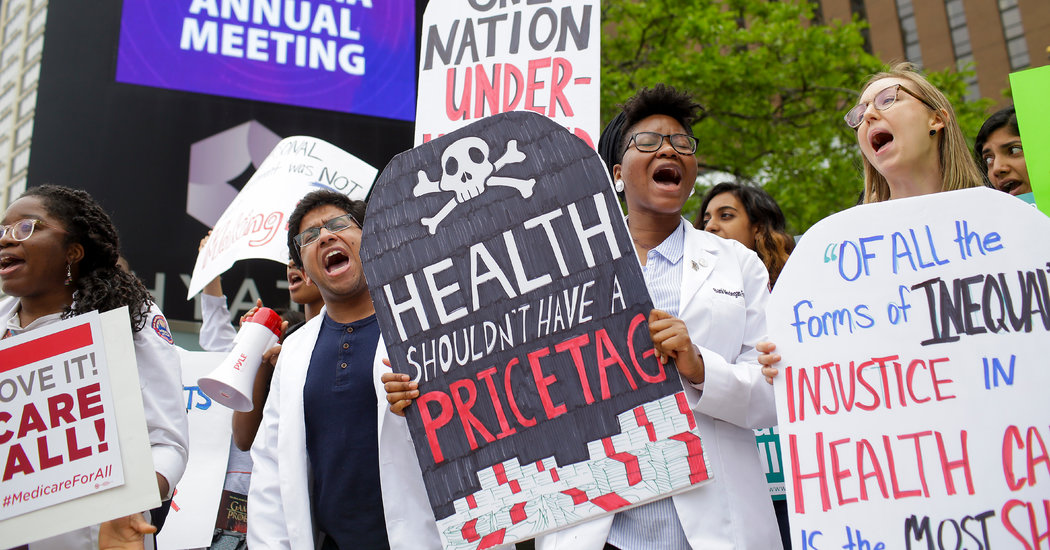

Public opinion surveys show that health care — particularly the cost of it — remains a top voter concern, reflected by the Democratic presidential candidates’ focus on Medicare for all and other proposals for expanding coverage to more people with a promise of lower direct costs. Congress is considering bills to help lower prescription drug costs and to eliminate the practice of surprise medical billing, though it is unclear whether either will pass this year.

The Trump administration is pursuing regulatory actions aimed at lowering health costs, including an ambitious rule that would require insurers and health care providers to disclose the prices they negotiate for a wide range of medical procedures and services. That rule, finalized last month, is being challenged in court by hospitals.

In the race for the Democratic presidential nomination, some candidates have been pushing far broader plans to tackle the issue. Senators Bernie Sanders of Vermont and Elizabeth Warren of Massachusetts have proposed establishing a single-payer health care system, where the government would provide generous taxpayer-funded insurance coverage for every American. Others, including former Vice President Joseph R. Biden and Mayor Pete Buttigieg, of South Bend, Ind., want to offer an optional government plan and more generous government subsidies for Americans who buy their own insurance.

However modestly it is growing, health spending in the United States is far higher than most other countries. The 2018 estimate of $ 3.6 trillion comes to more than $ 11,000 for every person in the country, with 33 percent going to hospital care, 20 percent to doctors and clinical services and 9 percent to retail prescription drugs. Measured as a percentage of gross domestic product, it is nearly double the average of health spending in other developed countries, according to the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development. Most of those countries achieve lower health costs with universal coverage. In the United States, an estimated 28 million people are uninsured.

Given the public outrage over prescription drug prices, many people may be surprised to find that prices of prescription drugs bought at a pharmacy actually fell by one percent in 2018 for the first time since 1973, economists with the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services said in a telephone briefing about the new report. President Trump has seized on the slight drop, mentioning it in his rallies and speeches, although some experts warn the method the federal government uses for tracking drug price trends is imperfect.

Overall averages obscure a volatile mix of prices, with some drugs commanding escalating price tags, even as more common generic medications became less expensive.

The report also found that the share of the American population with health insurance fell for a second consecutive year in 2018, with most of the enrollment decline — 1.3 million people — coming in private coverage purchased directly, instead of through a job or the Affordable Care Act marketplace. The Trump administration has repeatedly highlighted this population as victims of rising premium costs under the Affordable Care Act; they generally earn too much to qualify for its premium subsidies.

There was also a slight drop in the number of people with employer-sponsored insurance and slower growth in Medicaid enrollment, although growth in Medicare enrollment remained steady.

Spending for people with private health insurance was $ 6,199 a person, an increase of 6.7 percent over 2017, the highest per-person growth rate since 2004. That number does not include out of pocket costs.