Of the 16 million American adults who live with depression, as many as one-quarter gain little or no benefit from available treatments, whether drugs or talk therapy. They represent perhaps the greatest unmet need in psychiatry. On Tuesday, the Food and Drug Administration approved a prescription treatment intended to help them, a fast-acting drug derived from an old and widely used anesthetic, ketamine.

The move heralds a shift from the Prozac era of antidepressant drugs. The newly approved treatment, called esketamine, is a nasal spray developed by Janssen Pharmaceuticals Inc., a branch of Johnson & Johnson, that will be marketed under the name Spravato. It contains an active portion of the ketamine molecule, whose antidepressant properties are not well understood yet.

“Thank goodness we now have something with a different mechanism of action than previous antidepressants,” said Dr. Erick Turner, a former F.D.A. reviewer and an associate professor of psychiatry at Oregon Health & Science University. “But I’m skeptical of the hype, because in this world it’s like Lucy holding the football for Charlie Brown: Each time we get our hopes up, the football gets pulled away.”

The generic anesthetic is already increasingly available for depression, at hundreds of clinics around the country that provide a course of intravenous treatments, and studies suggest it can help treatment-resistant people. It often causes out-of-body and hallucinogenic sensations when administered; in the 1980s and 1990s it was popular as a club drug, Special K.

The cost for these treatments typically is out of pocket, as the generic anesthetic is not approved by the F.D.A. for depression. In contrast, esketamine likely would be covered under many insurance plans, and its side effects, though similar to those of generic ketamine, are thought to be less dramatic.

The recommended course of the newly approved drug is twice a week, for four weeks, with boosters as needed, along with one of the commonly used oral antidepressants. F.D.A. approval requires that doses be taken in a doctor’s office or clinic, with patients monitored for at least two hours, and their experience entered in a registry; patients should not drive on the day of treatment.

Esketamine, like ketamine, has the potential for abuse, and both drugs can induce psychotic episodes in people who are at high risk for them. The safety monitoring will require doctors to find space for treated patients, which could present a logistical challenge, some psychiatrists said.

The wholesale cost for a course of treatment will be between $ 2,360 and $ 3,540, said Janssen, and experts said it will give the company a foothold in the $ 12 billion global antidepressant market, where most drugs now are generic.

[Like the Science Times page on Facebook. | Sign up for the Science Times newsletter.]

The approval of esketamine marks a new approach to treating serious mood problems, experts said. Prozac and similar drugs enhance the activity of brain messengers such as serotonin; they are mildly effective, but they take weeks or months for their effects to be felt, and for many patients they provide little or no relief from depression. In contrast, the ketamine-based compounds — several others are being developed — work within hours or days, and are effective in some people who are considered “treatment resistant,” meaning they have not benefited from other antidepressants.

“These are exciting times, for sure,” said Dr. Todd Gould, an associate professor of psychiatry in the University of Maryland School of Medicine. “We have drugs that work rapidly to treat a very severe illness.” Dr. Gould was not involved in the Janssen study but has identified a metabolite, or ketamine breakdown product, that could be developed into another drug.

Experts with long experience in treating depression were encouraged by the news, but also chary. The effectiveness of the previous class of antidepressants such as Prozac and Paxil was vastly exaggerated when they came on the market. And the results of esketamine trials, which were paid for and carried out by Janssen, were mixed.

In each trial submitted, all patients were started on a new antidepressant drug, and given a course of esketamine treatment or a placebo. In one monthlong study, those on esketamine performed better statistically than those on placebo, reducing scores on a standard, 60-point depression scale by 21 points, compared to 17 points for placebo. But in two others trials, the drug did not statistically outperform placebo treatment. Historically, the F.D.A. has required that a drug succeed in two short-term trials before it is approved; the agency loosened its criteria for esketamine, opting instead to study relapse in people who did well on the drug.

In that trial, Janssen reported that only about one-quarter of subjects relapsed, compared to 45 percent of subjects who received the placebo spray. All the subjects had been given a diagnosis of treatment-resistant depression, or T.R.D., having previously failed multiple courses of drug treatment.

“We’ve had nothing new in 30 years,” said Steven Hollon, a professor of psychiatry and behavior sciences at Vanderbilt University. “So if this drug is an effective way to get a more rapid response in people who are treatment resistant, and we can use it safely, then it could be a godsend.”

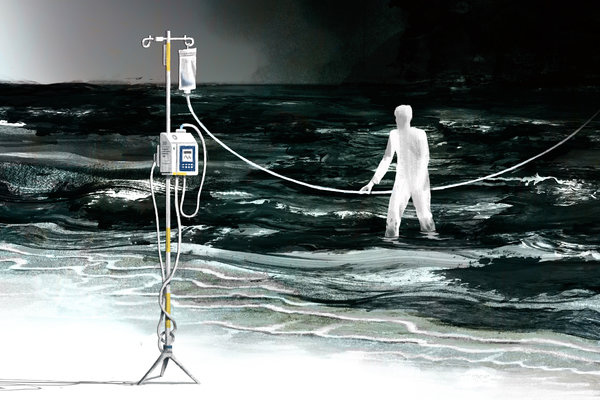

Desperate for relief

One question that will need to be answered is how well esketamine performs in comparison to intravenous ketamine.

Theresa, 57, an adjunct professor of English in New York, who asked that her last name be omitted to protect her privacy, has lived much of her life with deep depression. She tried a course of I.V. generic ketamine last summer, at a local clinic, which typically entails a half-dozen infusions, given over a couple of weeks, for about $ 500 apiece, with follow-up “booster” treatments as needed.

“I remember floating, I was really high,” she said. “I was tripping on sounds, textures and shapes, that was very much a part of it.”

The first infusion provided no relief, she said. But after the third or fourth, she noticed a satisfying “shift” in her underlying mood. “It’s a hard thing to describe. I was still anxious, but I felt somehow more solid, like something gelled within me, and my husband has noticed it, too.”

Dr. Glen Brooks, the founder and medical director of NY Ketamine Infusions, a clinic in downtown Manhattan, said he has treated some 2,300 people, of all ages, with intravenous ketamine, the generic anesthetic. His clients had received a variety of diagnoses, including post-traumatic stress, anxiety, and obsessive-compulsive disorder, as well as depression.

“What they all have in common is that other medications have failed,” Dr. Brooks, an anesthesiologist, said. “They’re hopeless, and they think, ‘Nothing else has worked, why should this?’” He said that, in his experience, the infusions quickly reduced symptoms for teenagers and young adults, but seemed to be less effective for people over 50.

The data that Janssen presented to the F.D.A. likewise suggested that esketamine was less effective in people aged 65 and older, barely better than placebo treatment.

Ketamine was developed more than five decades ago as a safer alternative to the anesthetic phencyclidine, or PCP, and is used worldwide, in operating rooms, on the battlefield and in pediatric clinics. The World Health Organization has listed ketamine as one of its essential medicines since 1985.

By the 1990s, interest turned to the drug’s potential to combat depression, when a government scientist named Phil Skolnick argued that targeting glutamate pathways — the primary “excitatory,” or neuroactivating, brain processes — could produce antidepressant effects. In 2000, a team of researchers at Yale University and the Connecticut Mental Health Center, led by Dr. Robert M. Berman, reported that doses of ketamine provided quick relief to seven people with depression.

The field took off in 2006, when a team at the National Institute of Mental Health led by Dr. Carlos Zarate Jr. reported that 18 treatment-resistant people who received the drug intravenously reported that their despair lifted within hours.

“What seems remarkable is that the drug also seems to help domains other than depression, like anxiety, suicidal thinking, and anhedonia” — the inability to feel pleasure — said Dr. Zarate, chief of the N.I.M.H.’s experimental therapeutics and pathophysiology branch. “It seems to have more broad effects, on many areas of mood.”

The apparent ability of ketamine to blunt suicidal thinking is particularly compelling, and Janssen is pursuing this indication for esketamine. In jails and psychiatry wards, suicide is an acute risk for people in crisis, and a fast-acting drug could save many lives, doctors said.

For now, no one knows whether esketamine, or any of the other ketamine-based compounds being studied, are any more effective than the generic anesthetic itself — or, for that matter, whether the out-of-body and hallucinatory “side effects” are in fact integral to its antidepressant properties.

“For that, we will need head-to-head studies,” Dr. Zarate said. “And we don’t have those yet.”